All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Indian Summer

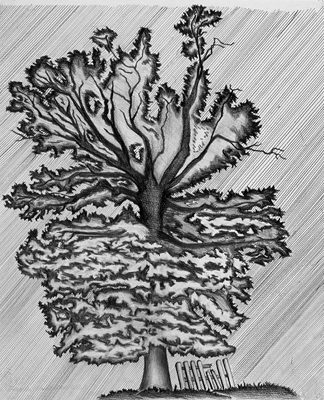

I have been fortunate enough to travel to Bangalore, India many times. Each trip, I found it growing up with me, from childhood to these teenage years. Going to India has given me a sense of who I am and the ancestral securities of which other children are deprived. When I first went to India, I was only one-year-old; after my birth, we made the journey every other year, and always returned home with fond memories. When I was around four, the one thing that I remembered most about India was its sweet, pure air. I remembered the trees always towering defensively over the houses of Bangalore and flowers tumbling from their strong and elegant branches to the dusty and muddied roads of the streets, making a floral pathway on the less than glamorous dirt roads.

I believe that it was those flowers that gave the air its purity. Sometimes, here in America, I would catch the slightest hint of that sweet Indian air and for that one second, I would stand and revel in the honeyed nostalgia.

My next batch of memories came at the age of nine. We had just landed at the airport, gathered our things and headed outside to find the van my uncle had rented for us. Almost immediately, I began searching for the sweet smell that I knew all too well.

I couldn’t find it.

What I found was the cacophony of a thousand cars, motorcycles, and auto-rickshaws secreting a dark, musky smoke as they sputtered up and down the street. It was funny; they had never seemed so loud before.

We met up with my uncle a little while later. Normally, we would hug, kiss, enquire into each other’s health, et cetera et cetera, but at one o’clock in the morning, we put the pleasantries on hold. Instead, we said a quick hello to my uncle Bushna, loaded the ten tons of luggage into the trunk and took off. I looked from the window as we drove through the claustrophobic roads: the trees that had lined the streets were gone. Instead, buildings, shopping centers, and other monstrosities had replaced them and I began to feel as though a dark and threatening storm loomed ahead.

The next time we went, I was eleven and in the sixth grade. I was busy, mature, and had better things to do in life than be a child. India had mirrored my personality. Almost nothing was left of what I had known. I only knew the New India of crowded streets and high-rise apartments. I didn’t notice the changes, though, for I had grown up.

This time, we visited our relatives to invite them to an occasion that I myself knew near to nothing about: my Upanayanam, the South Indian coming-of-age ceremony. With all the driving we were logging in, the congested streets became a thing of normalcy and didn’t bother me as much as I thought they would have. This Upanayanam would be my official inauguration into the real world, the one in which you are on your own. This Upanayanam would be India’s inauguration into the real world.

As soon as that day was over, I would have left the world of flowered streets and defensive trees, and I would have to fend for myself. The trees would have to let me go on, their purpose changing from being the walls of my world to the reminders of my past. They too, would have to fend for themselves. They bordered my world no longer.

So the days went by as we travelled routinely from house to house, from temple to temple, all in preparation for that vital moment that would deliver me from the ignorance of my childhood and into the ranks of adulthood. I counted down the days, imagining my life after it all happened.

But I also felt a nagging, a calling if you will, that dampened my excitement. I looked around at the New India one day from the balcony of my grandparents’ house and, for the first time, realized how different it was from the India of my childhood. I saw myself walking up and down my grandparents’ street as a child. I saw the shady trees swaying back and forth. I saw the flowers snowing down to line the streets once more.

I smelt the pure air that used to be everywhere.

But it was for only but a moment and I was thrown back into the world at present. I saw nothing walking up and down the streets but stray dogs and lumbering cows that went mournfully along. I saw no trees swaying lazily back and forth, only new houses being built in their place. No flowers snowed from above, only the heat radiating from the sun. I smelt no pure air, only smoke and irritation.

The day had come. I woke up at dawn to get ready for the event. I was given milk for breakfast as my father explained to me the meaning of this day. He said that today would be the day that I would become a young man worthy for higher education, a job, and a respectable life; I just sat there listening in groggy indifference. Tired though I was, somewhere in the farthest reaches of my mind, the words my father was saying rang loud and true. He had confirmed what I had imagined all this time. The real world truly awaited my arrival, and it was my duty to accept it.

If there is one thing that any person must know about India, it’s that its mornings are the most beautiful that you will ever experience. Cars and motorcycles don’t contaminate the air with the sound of a thousand horns; instead the air is laden with the sound of songbirds coming out from their hiding spots to perform their ancient melody. This was Bangalore’s morning glory, the mornings in which the pure air had room to exist and waft underneath my nose and whisper secrets of Old India in my ear.

We reached the hall where the ceremony was to take place ten minutes later. My grandmother, cousin, mother, and I filed out. We paid the driver his due, hoping he hadn’t rigged it like some of the other rickshaw drivers. The air caressed my face one final time and then disappeared as city and nation woke from their slumber. That pure air, that last remnant of the Old India, moved on.

The ceremony was to begin soon, but my stomach was wailing out of hunger. I complained to my grandfather who, in turn, snuck me into the kitchens. I knew I wasn’t supposed to eat anything before the ceremony, but my stomach fiercely disobeyed convention. The head cook took pity on me and gave me idlis to eat until I was sufficiently full. Well, sufficiently half-full really.

With no further ado, the ceremony began. The priest began to chant as I watched, my legs already growing sore on the wooden platform I was sitting on. The sun rose higher and higher into the sky as more and more people came to watch me fumbling over the prayers I had to say. The entire thing was made worse by the fire and glaring light from the video camera in front of me burning my face off. For several hours, I endured it, with a brief respite to stretch my numbed legs. The sun had reached high noon and was going down slowly and elegantly. The Upanayanam finally came to a close, with one last prayer for me to recite. Of course, I fumbled over that as well.

So it was over. My initiation into the real world was complete. My burning face had cooled down. I decided to go outside and look at the New India. What I saw before me was something that I could never express with words. India had grown with me. Just as I transcended my world and India had done so along with me. Every time I had come here, India and I had grown a just a little bit. Now, after this, India and I were ready to face whatever the world threw at us.

That was the last trip to India; it has been three years since we’ve gone. India and I have moved on with our lives, not thinking about each other as much as we used to. From time to time, I reminisce on my travelling days. I think of the air, the trees, and the flowered streets. I may have been born in America, but those trips have kept me firmly rooted to my heritage. Those trips helped me face the real world. India gave me my identity. Since then, the Old India has left me, but once every now and then, I seem to catch a hint of a pure, sweet air. I stop and search for it, but never find it. I just move on.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.